What I Watched and Rewatched: Spring ‘25

Woah, it’s been a minute, eh? Yeah, sorry. I’ve been busy. Anyhow, another month of movie-watching, another month documenting what I’ve watched.

Woah, it’s been a minute, eh? Yeah, sorry. I’ve been busy. And I’ll also concede that, after a while, I couldn’t sustain juggling a cutthroat monthly recap schedule with other, frankly, more important endeavors. So, here’s my part compromise, part solution: From now on, these “What I Watched and Rewatched” posts will be seasonal. Additionally, I’m dedicating individual recaps to contemporary releases and older films, which should give me more of an excuse to ramble on about the state of the industry and whatnot. Sounds good?

Alright, to set a few guidelines for what films qualify for this post: (1) They must’ve been viewed between March 21st and June 21st. (2) No films released this year qualify for the recap. So, all the films here are either canonical oldies that I’ve yet to see or revisits that I haven’t watched in a while. (3) All these reviews are ripped straight from my Letterboxd account. Now, here’s the rundown.

Donnie Darko (2001, Richard Kelly)

[Mar. 29th, 2025; 89/100:] I remember being wholly unprepared for the unhinged, occasionally amateurish chaos of Richard Kelly’s second feature follow-up, Southland Tales (2006), but after rewatching Donnie Darko, maybe I shouldn’t have. For a movie that’s renowned for its “What the fuck am I watching?” surrealism and perplexing narrative logic, the Reagan-America suburbia satire is laid thick here. (Think an extreme verisimilar-fusion of a Blue Velvet-adjacent atmosphere and John Hughes’ formal aesthetics. Also, no wonder Kelly recently retweeted a picture of David Lynch and John Waters; his entire body of work is strikingly transgressive, which I didn’t register as clearly when I first watched Donnie Darko.) But unlike many Lynchian-wannabes who only impersonate the director’s dreamlike aesthetics and stylized, non-sequitur dialogue technique, Kelly miraculously captures Lynch’s sincerity, as well. There are so many sequences where the film suddenly interjects a moment of genuine, emotional earnestness amidst an ambiance of relentless dread, making its sentiments of teenage nihilism hit like a punch to the stomach. For a movie about adolescent suicide, Darko’s solution to “breaking canon,” to leave this world behind—something that is not left to interpretation whatsoever—is harrowingly bleak; the idea that the world’s underbelly is so repulsive, where incompetence reigns supreme, and we can’t do anything about it.

Happiness (1998, Todd Solondz)

[Apr. 25th, 2025; 71/100:] I’ve spent an unreasonable amount of time trying to describe Happiness in a blurb, and here are the two I came up with. First: Imagine American Beauty (1999) if it were infinitely more transgressive and edgy. As if the pedophile subplot in Sam Mendes’ feature breakthrough wasn’t queasy enough, Todd Solondz’s hyperlink narrative of arrested sexual dysfunction has ideas so repulsive, it had me saying, “What the fuck?” at least 50 times in the first hour alone. (The shock-induced whiplash I got from Philip Seymour Hoffman’s character saying, “I want to tie her up and pump her, pump, pump, pump, ‘till she screams bloody murder” is equivalent to having a car crash head-on into you.) It’s almost “internet-core” black comedy—stuff you’d only find on the deep ends of 4chan—only this was made years before so-called internet humor became a thing. I’m nonetheless skeptical, if not outright doubtful, of the possibility that this film has any deeper meaning beyond its skin-deep suburban dysphoria. But I suppose it deserves some flowers for foreseeing a sort of comicness that’s omnipresent in today’s world. Second: Imagine if Robert Bresson had the perverted mind of John Waters. When I read that Solondz’s Wiener-Dog (2016) took conceptual inspiration from Au hasard Balthazar (1966), it clarified some things for me. Sure, that anecdote doesn’t technically affirm my Bresson suspicions, but from a composition and movement standpoint, I immediately thought of Bresson’s obsession with formal efficiency.

Only Angels Have Wings (1939, Howard Hawks)

[May 16th, 2025; 83/100:] I was pulled in two directions before attending my 4:00 p.m. screening. On one hand, Mike D’Angelo, my go-to film critic for several years now, calls this his favorite film. On the other hand, a friend who has loved many of Howard Hawks’ films and likes Only Angels Have Wings well enough isn’t sure if he’d place this in the top five of Hawks’ filmography. Then again, he hadn’t seen the movie in a while, decades presumably, and was open to changing his opinion this time around. And now that I’ve seen the film in an ideal setting—a large screen, a gorgeous digital restoration, with a great sound system, to boot—yeah, I don’t see the vision here. While reading some reviews from the people I follow, I’ve noticed loads of praise for Cary Grant’s performance as Geoff Carter, but I’ll co-sign my friend’s opinion here and say he’s frustratingly all over the place, execution-wise. At his best, Grant’s on-screen magnetism bodes well with a man who’s trying to repress his true thoughts and feelings. At his worst, when leaning into this His Girl Friday-esque (1940), quick-talking mode of acting, he almost feels miscast, and I had a hard time separating the actor from the character. Thomas Mitchell, on the other hand, really blew me away. The way Hawks lights this sucker certainly does Mitchell favors, but his eyes are incredibly expressive. So much so that every time he was on screen, which was pretty frequently, might I add, I was dead-focused on his eyes, where they moved, etc.

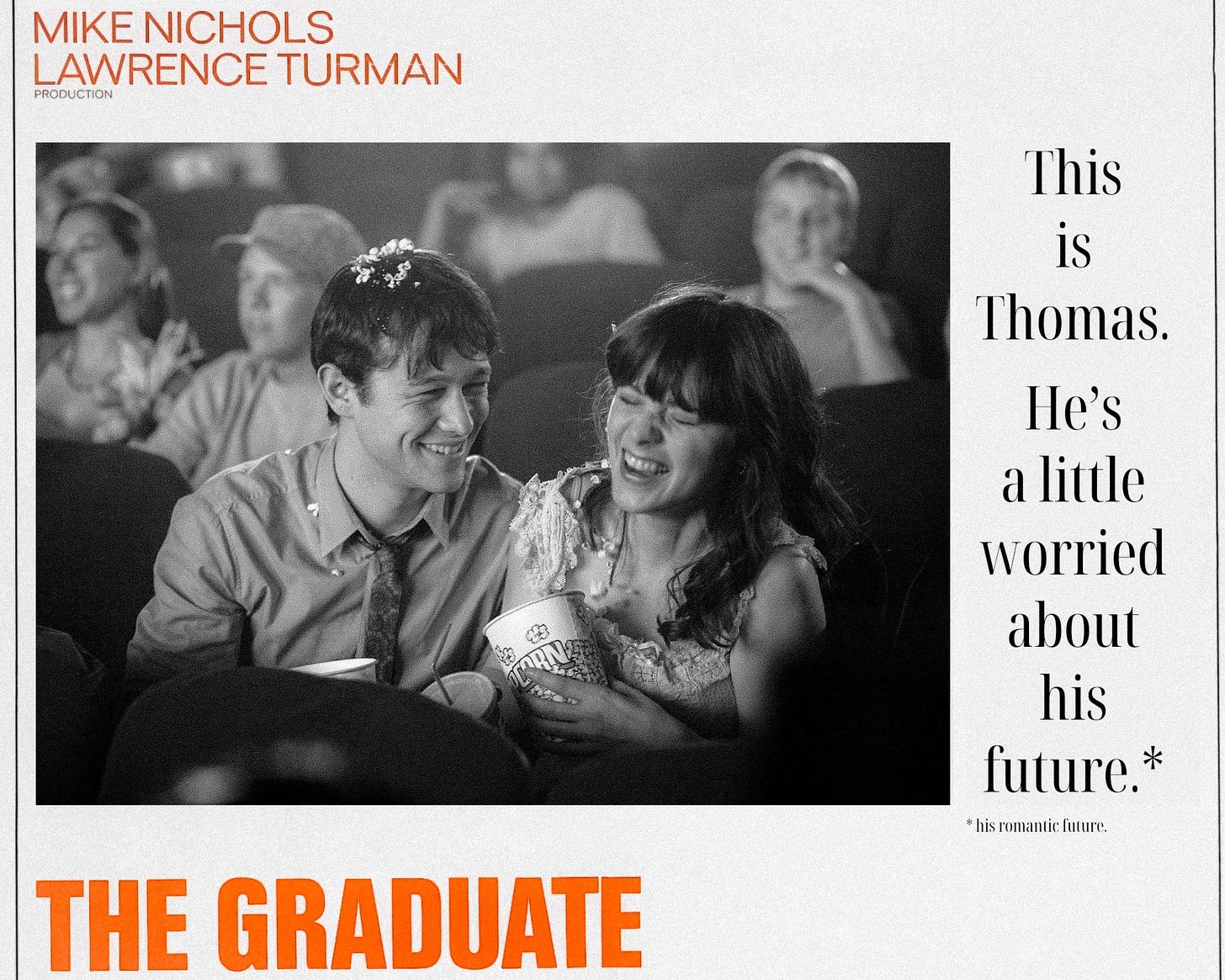

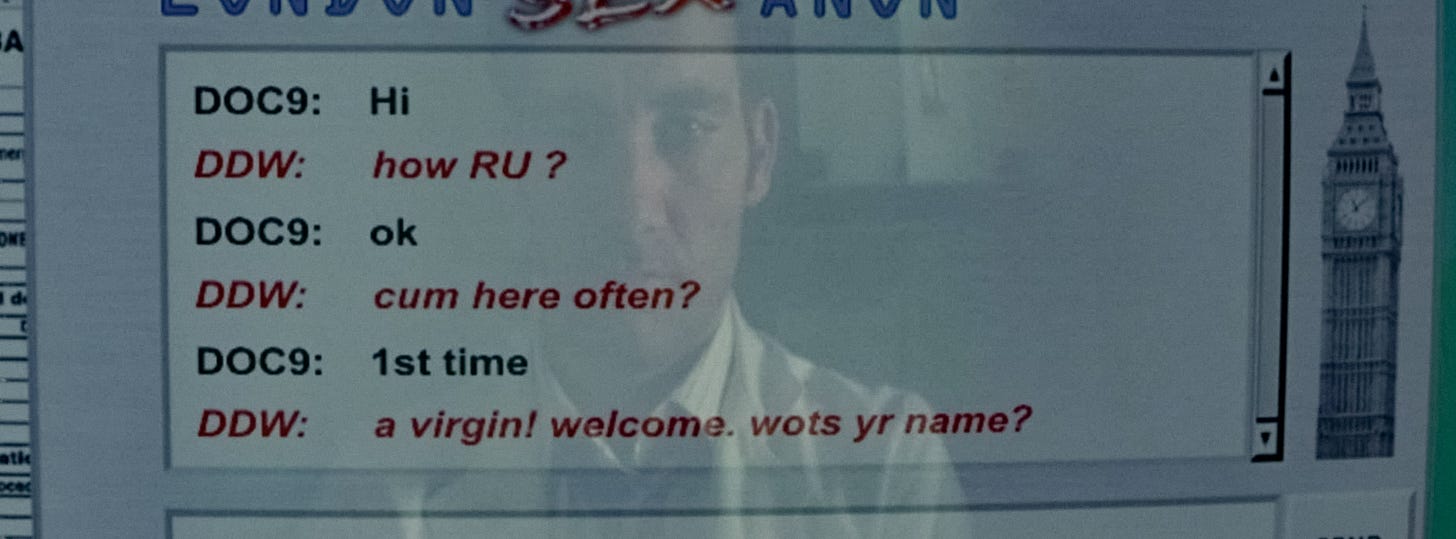

Closer (2004, Mike Nichols)

[May 18th, 2025; 74/100:] Like The Graduate (1967) almost forty years before, but for fully-fledged yet fully-dysfunctional “adults,” Closer unravels with a stunner of an opening. Two people, amongst a hundred others, eyes locked, gazes set, inching just a bit closer to each other. While what follows isn’t outright revealed to us until the movie’s end, one line from Jude Law’s Daniel Woolf perhaps best epitomizes what the fuss is about. “I said, ‘Yes, she’s mine.’ She’s mine.” A seemingly sweet declaration of romanticism that simultaneously displays every red flag in the book. Yet, it’s the kind of self-destructive toxicity that I find so alluring on screen. Even the scene of the cybersex chat room, in all its melodramatic and semi-transgressive glory—heightened by its operatic soundtrack—is genuinely transfixing and quite hilarious, as if Mike Nichols somehow recaptured the young-and-restless, lightning-in-a-bottle magic of The Graduate. However, had a younger Nichols been behind the camera, I’d almost certainly buy into the small-but-loud sentiment that staunchly believes this is some overlooked masterpiece. Not that it’s “formally unadventurous,” as Mike D’Angelo said about Nichols’ filmography post-Heartburn (1986), but the visual details aren’t as striking—e.g., neat pans, some sporadically showy blocking, but little else—and I doubt he’d commit the same sort of formal blunders. This movie has some utterly bizarre editing choices; no visual cues to signify the repeated passage of time is such an egregious cinematic offense; you can only get away with that if you’re writing a stage play with lengthy set pieces, which this is so clearly based upon.

Wild at Heart (1990, David Lynch)

[Jun. 4th, 2025; 46/100:] Sorry, I didn’t get much of anything outta this. Something like Twin Peaks (1989) or Mulholland Drive (2001), I find to be palpably sincere; David Lynch has so much love for those minute moments of humanity, his ensemble’s complexities, the good and evil of the world, and its support structures, which the end-product makes forthright. I don’t sense that here. Instead, Wild at Heart, with its melodramatic surrealism, its bliss for hedonism, and its mean-spirited violence, feels distractingly self-aware of its campy trashiness. I occasionally find myself frustrated by some of Roger Ebert’s reviews—please don’t get me started on his ridiculous pre-revisionism comments on Lynch and Abbas Kiarostami—but I found his otherwise lukewarm observations of Wild at Heart, which he described an elaborate, provocative “joke,” astute and pretty damn spot-on. After all, judging by how Lynch frames his camera, there’s so much contempt on display. Even the over-the-top romanticism between Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern’s characters felt ridiculous and completely insincere, which seems to be an unpopular opinion, but hear me out. Take the ending, for example. I assume the sort of daydreamy quality of the final scene and Sailor’s aggrandized declaration of love, as Cage jumps on top of a slew of cars and sings Love Me Tender, was supposed to be moving. But I felt wholly alienated by the experience. I felt pushed beyond arm’s length.

Blood Simple (1984, Joel Coen)

[Jun. 5th, 2025; 94/100:] If I had to guess, I assume Blood Simple’s uber-lean narrative construction prevents people from calling this a first-rate Coens film, but does that matter when the craft is so good? This is seriously unimpeachable filmmaking and screenwriting, down to the smallest of details. Even the opening’s use of the phrase “marriage counselor” is textually rich; so efficiently does its use and re-use establish the dynamics between this love triangle, what’s understood and what’s not, whether or not they see eye-to-eye with each other, that the movie practically speedruns its way into an inciting incident in complete stride. In any other circumstance, something like this would be found at the apex of a great director’s career. This is their debut feature. And the Coens make it look so easy, as well. Somehow, I haven’t yet mentioned all the striking, noir-inspired images that Blood Simple has in spades. Rarely do you see any director’s early work feature ideas that are so judiciously confident, with formal trickery that’s not just showy for the sake of being showy but also ingeniously motivated, with film grammar that continuously plays with the audience’s expectations. I especially love the one shot of Frances McDormand’s Abby getting up and down from bed. It’s pretty basic blocking and staging, with the window behind Abby instinctively giving the audience pause, but it’s the editing that makes all this especially revelatory. The Coens make one cutback shot—at approximately the 31:36 mark—linger just a second longer than usual, which almost looks like an error at first glance, but it winds up being a tool of unease before the real suspense kicks in. Again, brilliant stuff.

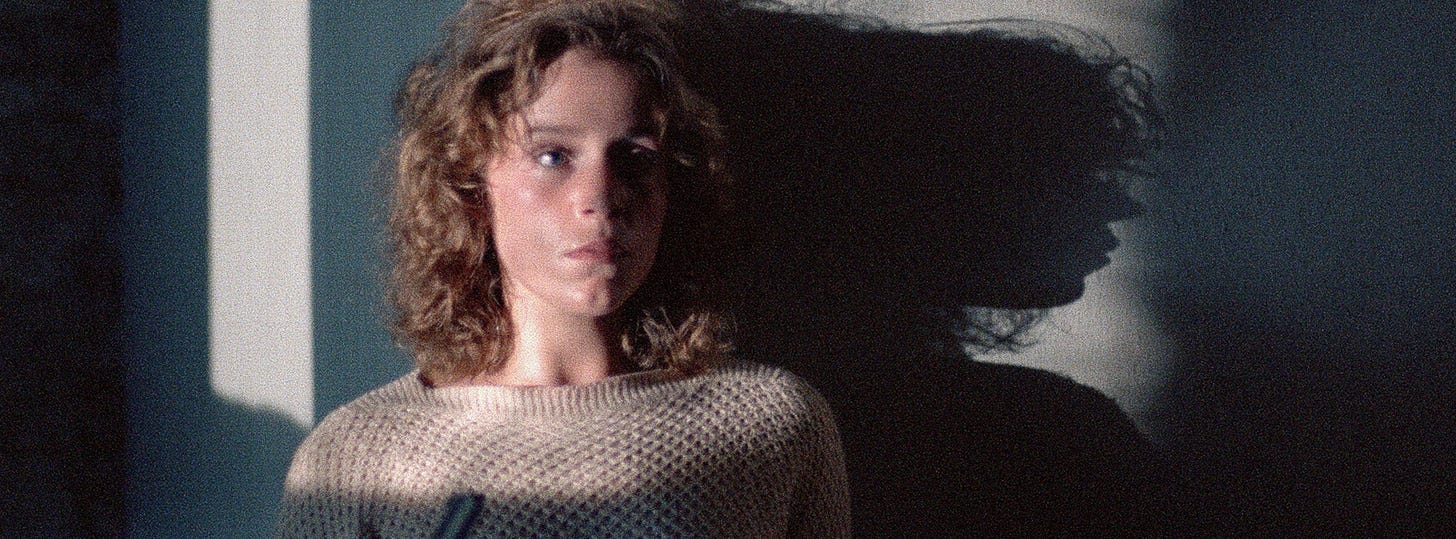

The Virgin Suicides (1999, Sofia Coppola)

[Jun. 8th, 2025; 81/100:] I think the Tumblr-ification of The Virgin Suicides greatly undermines its much-deserved title as a “Bleak Week” movie. While Sofia Coppola’s now-trademark visual aesthetic softens the blow of an otherwise upsetting story, the narrative premise unsettles me more by the minute. It’s, quite simply, a scathing portrait of humanity and the men who treat the perspective of young women as a complete afterthought. And while there’s a male-gazey quality to the source material, I’m wholly fascinated by the constant tug-of-war between Sofia Coppola’s visual language and the words of Jeffrey Eugenides. The visuals, the act of actually seeing these boys engage in their voyeurism, with motives rendered oblique by messy adolescence, portray them as a little pathetic and misguided. Their long exhales. Their awkward conversations. Their make-outs-gone-wrong. It’s a little hard to watch, and I’d assume that was all intentional. And yet, they were the only ones who at least had a shred of empathy for the girls, which is such a dizzying thought. James Woods is exceptionally memorable as the good-willed, though equally clueless, father. However, I genuinely found Kathleen Turner’s paranoia-driven performance as the mother some otherworldly kind of evil. And let’s not forget the numerous sequences of the town’s local news making a spectacle out of suicide or the drunken, backhanded mockery of someone saying, “You don’t understand me! I’m a teenager! I’ve got problems!” That really pinched a nerve.

Incendies (2010, Denis Villeneuve)

[Jun. 10th, 2025; 73/100:] Let’s calm it with the Kubrickian disciple-isms, please? Look, it’s undoubtedly a fool’s errand to question Denis Villeneuve’s talents as a director—he knows how to compose a stunning picture—but perhaps it’s better to address his shortcomings as a storyteller? There’s no getting around it: Incendies is bleak stuff. What starts as an air-tight family drama reveals itself to be an expansive journey into the powerless cruelty of the world around us. And I guess that fascinates Villeneuve, considering that his next feature effort is equally somber, Prisoners (2013), even though that film is straight-up stupider in narrative craft. But bleak cinema shouldn’t always equate to “cold” filmmaking, and many technical choices here rubbed me the wrong way. For a story that supposedly wallows in the intensely personal, the formal choice to keep me at arm’s length from the material at all times is a frustrating one. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say I felt emotionally indifferent to the minute-to-minute happenings for almost 75% of the movie, and I don’t think any scene better exemplifies this than the phenomenally choreographed bus sequence. It’s intensely immersive and foreshadows the blockbuster talent that is to come. But when the child runs back to the burning bus, Villeneuve inexplicably cuts to a withdrawn ultra-wide shot of the child being shot to death. You can argue this decision regurgitates his fascination with power or the lack thereof, but why would one suck all the emotion out of such a gut-punching moment? It’s not like it’s impossible to communicate both things at once; look at what Atom Egoyan did with The Sweet Hereafter (1997). I think the closing stretch won me over a little as things started to piece together. (I don’t think the twist is ridiculous or unearned, at least on this viewing.) But the ramifications of the twist don’t reverberate backward for me and make me second-guess everything that precedes it.

28 Days Later (2002, Danny Boyle)

[Jun. 18th, 2025; 72/100:] A really fascinating film in hindsight for a multitude of reasons. One, because its cast of Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, and Brendan Gleeson were complete nobodies to us American audiences at the time of release. And now, they’re all Oscar nominees or winners. Yet, their current standing as household names doesn’t quite distance me from the plot’s immersion, which can probably be attributed to all three being, at heart, immense character actors. Two, its technical elements. Many films before and after 28 Days Later leaned heavily into the visual defects of 480p digital technology, but I can’t think of one that better infuses this aesthetic into tactile and apocalyptic world-building. It’s the kind of movie that could only be made in the early 2000s; you didn’t have to think twice about whether something was being shot on film or digital. (To anyone curious, Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000), David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006), and even Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000) are good, grainy reference points.) Because of this, I wonder, skeptically, if Danny Boyle can pull the same magic trick twice over with 28 Years Later. That’s being shot on an iPhone, but for all its limitations, the results look far better than whatever those 480p cameras were capable of over two decades ago. Perhaps the answer is through frenetic movement? Or editing? I’ll have to wait and see. Other than that, I don’t have much else to add from my previous review. I stand by what I said three years ago.

The Rules of the Game (1939, Jean Renoir)

[Jun. 18th, 2025; 94/100:] The Rules of the Game’s opening act is a really tough ask—there are so many moving parts, so many interlinked dynamics and faces to remember—but this sucker was something to behold once I got to its wavelength. For one, this has some of the most seamless tonal shifts I’ve ever seen. The sequence where the ensemble kills off the rabbits, for example, so naturally veers into unsettling territory, but it’s the nonchalant depiction of such violence that prevents the scene from being haphazardly injected within the flow of the story. (Before that, much of the build-up is unmistakably chaotic but in a comparatively “light” manner. I mean, the core setup is constructed around people being romantically entangled with other people, not death.) Yet such blunt cruelty pales in comparison to when Jean Renoir tonally restyles The Rules of the Game into a chambered, deprived clusterfuck, which is wicked entertaining. Everybody’s gotta problem with everybody, and for approximately 40 minutes, it’s one of the funniest and sharpest satires out there. In its chaos, I got vague flashbacks to my experience watching Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration (1998), not necessarily through its conceptual framework but more through how it captures a slow-motion car crash that you can’t look away from in repulsive detail. Shit goes horribly wrong, and it has no right to be as enthralling as it is. It also helps to have some zippy camerawork to crank up the freneticism, which this has in spades. And while most of Renoir’s movements wouldn’t be classified as “showy” by today’s standards, the blocking is effortlessly precise. I’m almost certain that this was the definitive blueprint for someone like Robert Altman.